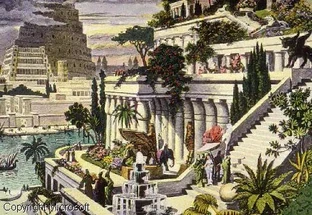

16th Century depiction of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon

The history of gardening and growing ornametal plants spans thousands of years, going back to ancient Egypt and Persia. Over the centuries, gardens have been used as dispays of art, status, national pride, affection and scholarly wisdom.

Overview

Forest gardening is the world's oldest form of gardening. Forest gardens originated in prehistoric times along jungle-clad river banks and in the wet foothills of monsoon regions. In the gradual process of families improving their immediate environment, useful tree and vine species were identified, protected and improved whilst undesirable species were eliminated. Eventually superior foreign species were selected and incorporated into the gardens.

After the emergence of the first civilizations, wealthy individuals began to create gardens for purely aesthetic purposes. Egyptian tomb paintings of the 1500s BC are some of the earliest physical evidence of ornamental horticulture and landscape design; they depict lotus ponds surrounded by symmetrical rows of acacias and palms. Another ancient gardening tradition is of Persia: Darius the Great was said to have had a "paradise garden" and the Hanging Gardens of Babylon were renowned as a Wonder of the World. Persian gardens were also organized symmetrically, along a center line known as an axis.

Persian influences extended to post-Alexander's Greece: around 350 BC there were gardens at the Academy of Athens, and Theophrastus, who wrote on botany, was supposed to have inherited a garden from Aristotle. Epicurus also had a garden where he walked and taught, and bequeathed it to Hermarchus of Mytilene. Alciphron also mentions private gardens. The most influential ancient gardens in the western world were the Ptolemy's gardens at Alexandria and the gardening tradition brought to Rome by Lucullus. Wall paintings in Pompeii attest to elaborate development later. The wealthiest Romans built extensive villa gardens with water features, topiary and cultivated roses and shaded arcades. Archeological evidence survives at sites such as Hadrian's Villa. Byzantium and Moorish Spain kept garden traditions alive after the 4th century AD and the fall of Rome. By this time a separate gardening tradition had arisen in China, which was transmitted to Japan, where it developed into aristocratic miniature landscapes centered on ponds and separately into the severe Zen gardens of temples.

In Europe, gardening revived in Languedoc and the Île-de-France in the 13th century. The rediscovery of descriptions of antique Roman villas and gardens led to the creation of a new form of garden, the Italian Renaissance garden in the late 15th and early 16th century. The first public parks were built by the Spanish Crown in the 16th century, in Europe and the Americas. The formal Garden à la française, exemplified by the Gardens of Versailles, became the dominant style of garden in Europe until the middle of the 18th century when it was replaced by the English landscape garden and the French landscape garden. The 19th century saw a welter of historical revivals and Romantic cottage-inspired gardening. In England, William Robinson and Gertrude Jekyll were strong proponents of the wild garden and the perennial garden respectively. Andrew Jackson Downing and Frederick Law Olmsted adapted European styles for North America, especially influencing public parks, campuses and suburban landscapes. Olmsted's influence extended well into the 20th century.

The 20th century saw the influence of modernism in the garden: from the articulate clarity of Thomas Church to the bold colors and forms of Brazilian Roberto Burle Marx. A strong environmental consciousness and Sustainable design practices, such as green roofs and rainwater harvesting, are driving new considerations in gardening today.

Gardens in Antiquity

Egyptian Gardens

Rectangular fishpond with ducks and lotus planted round with date palms and fruit trees, in a fresco from the Tomb of Nebamun, Thebes, 18th Dynasty

Gardens were much cherished in the Egyptian times and were kept both for secular purposes and attached to temple compounds. Gardens in private homes and villas before the New Kingdom were mostly used for growing vegetables and located close to a canal or the river. However, in the New Kingdom they were often surrounded by walls and their purpose incorporated pleasure and beauty besides utility. Garden produce made out an important part of foodstuff but flowers were also cultivated for use in garlands to wear at festive occasions and for medicinal purposes. While the poor kept a patch for growing vegetables, the rich people could afford gardens lined with sheltering trees and decorative pools with fish and waterfowl. There could be wooden structrures forming pergolas to support vines of grapes from which raisins and wine were produced. There could even be elaborate stone kiosks for ornamental reasons, with decorative statues.

Temple gardens had plots for cultivating special vegetables, plants or herbs considered sacred to a certain deity and which were required in rituals and offerings like lettuce to Min. Sacred groves and ornamental trees were planted in front of or near both cult temples and mortuary temples. As temples were representations of heaven and built as the actual home of the god, gardens were laid out according to the same principle. Avenues leading up to the entrance could be lined with trees, courtyards could hold small gardens and between temple buildings gardens with trees, vineyards, flowers and ponds were maintained.

A funerary model of a garden, circa 2009–1998 BC.

The ancient Egyptian garden would have looked different to a modern viewer than a garden in our days. It would have seemed more like a collection of herbs or a patch of wild flowers, lacking the specially bred flowers of today. Flowers like the iris, chrysanthemum, lily and delphinium (blue), were certainly known to the ancients but do not feature much in garden scenes. Formal boquets seem to have been composed of mandrake, poppy, cornflower and or lotus and papyrus.

Due to the arid climate of Egypt, tending gardens meant constant attention and depended on irrigation. Skilled gardeners were employed by temples and households of the wealthy. Duties included planting, weeding, watering by means of a shaduf, pruning of fruit trees, digging the ground, harvesting the fruit etc.

Persian Gardens

All Persian gardens, from the ancient to the high classical were developed in opposition to the harsh and arid landscape of the Iranian Plateau. Unlike historical European gardens, which seemed carved or re-ordered from within their existing landscape, Persian gardens appeared as impossibilities. Their ethereal and delicate qualities emphasized their intrinsic contrast to the hostile environment.

The heart of Persia, modern day Iran, is high and dry. A series of basins and plateaus are separated by the two main mountain ranges, the Albourz and the Zagros. Since ancient times, lush gardens have grown in the region due to an ingenious engineering system of underground aqueducts called qanats. Originating in northeastern Iran around 800 BC, qanats brought the water from the snow melt to the plains for irrigation and human use. The very presence and abundance of water became the essence of the Persian garden. A rich variety of species thrived while thin channels delivered water throughout the garden, feeding fountains and pools, cooling the atmosphere and providing tender, constant music in the air. Although gardens were places for poetry, contemplation and seclusion, they were not limited to pleasure and refuge. Throughout Persia's history, gardens were central to the political life of the ruling class. The Achaemenian king Cyrus placed his throne within his garden at Pasargadae. Persian miniature paintings from the 15th to the 17th century depict kings receiving diplomats in their gardens, treaties being signed there, feasts and celebrations, and all defining moments of national identity along with portrayals of legendary loves. The illustrated history, Shahnameh, Book of Kings, details both the dreamy and the practical in court life.

The ancient gardens before Cyrus and those of his descendants show evidence of the characteristics that continued to define gardens in Persia and in places that drew on Persian ideas, from India to Spain. Gardens typically were divided into quadrants by channels of water, often punctuated by geometrically shaped basins. At a central intersection point was a platform for viewing, which later evolved into a formal open pavilion, sometimes decorated with coffered ceiling structures that represented the complexity of the heavens. Geometry as a demonstration of the ordered universe was celebrated throughout Persian gardens from the surface design features to the basic ground plane and its fourfold chahar bagh format, representing the four corners of the world in the ancient vernacular, and the four rivers of paradise more predominately associated with the Islamic period. The roots of an earthly paradise however, originate in Mesopotamia thousands of years before the Achaemenians, long before the Islamic period. Persian design aspects proved to have a natural affinity to certain Islamic concepts but because they were so deeply embedded in the culture of the area, they maintained their Persian-ness throughout the country's tumultuous history. The relationship of architecture to the Persian garden is layered; influenced by climate and geography and infused with a sense of the ephemeral qualities of light and reflection. The border between interior and exterior spaces was permeable and often transparent through the use of carved screens, deep archways, multiple vaults and honeycomb patterned ceilings punctured with tiny windows of light. Through these devices, the stone, mud and ceramic materials appear as delicate and malleable as paper, conveying the fugitive qualities of light and shadow while playing with what is revealed and what is veiled.

Classical Persian gardens were lived spaces; one imagines that they are best seen from within. As 17th century European gardens expressed the concept of a privileged point of view as demonstrated in Renaissance painting, Persian gardens can also be viewed in relation to their classical tradition of painting during the Safavid period, contemporaneous of the European Renaissance. Where the space of the paintings appears flat and perplexing, a balance is found in multiple entry points and equal attention to every detail whether it is the king's action, a servant's gesture or the ruby red of a bowl of pomegranates. Despite a hierarchical, feudal society, everything is painted equally and in sharp focus. As the viewer, you are at once, inside and everywhere. The Islamic gardens of Spain constructed during the 14th century are far more elaborate and extensive than northern European gardens of that period. Featuring open garden rooms, intricate tile designs, water features and sculpture, the designs were influenced by the Moors. Unlike the medieval gardens depicted above, these gardens were ornate outdoor spaces where members of the court could convene and cool themselves from the intense heat of the sun. The Alhambra Palace as well as the Generalife gardens that surround the palace in Granada, Spain survive today as well-preserved examples of the mark of Arabic culture on Spanish architecture and landscape design.

Hellenistic Gardens

It is curious that although the Egyptians and Romans both gardened with vigor, the Greeks did not own private gardens. They did put gardens around temples and they adorned walkways and roads with statues, but the ornate and pleasure gardens that demonstrated wealth in the other communities is seemingly absent.

Roman Gardens

Reconstruction of the roman garden of the House of the Vettii in Pompeii

Roman gardens were a place of peace and tranquillity, a refuge from urban life. Ornamental horticulture became highly developed during the development of Roman civilisation. The administrators of the Roman Empire (c.100 BC - AD 500) actively exchanged information on agriculture, horticulture, animal husbandry, hydraulics, and botany. Seeds and plants were widely shared. The Gardens of Lucullus (Horti Lucullani) on the Pincian Hill on the edge of Rome introduced the Persian garden to Europe, about 60 BC.

Byzantine Gardens

The Byzantine empire span a period of more than 1000 years (330-1453 AD) and a geographic area from modern day Spain and Britain to the Middle East and north Africa. Probably due to this temporal and geographic spread and its turbulent history, there is no single dominant garden style that can be labeled "Byzantine style". Archaeological evidence of public, imperial, and private gardens is scant at best and researchers over the years have relied on literary sources to derive clues about the main features of Byzantine gardens. Romance novels such as Hysmine and Hysminias (12th century) included detailed descriptions of gardens and their popularity attests to the Byzantines’ enthusiasm for pleasure gardens (locus amoenus). More formal gardening texts such as the Geoponika (10th century) were in fact encyclopedias of accumulated agricultural practices (grafting, watering) and pagan lore (astrology, plant sympathy/antipathy relationships) going back to Hesiod's time. Their repeated publications and translations to other languages well into the 16th century is evidence to the value attributed to the horticultural knowledge of antiquity. These literary sources worked as handbooks promoting the concepts of walled gardens with plants arranged by type. Such ideals found expression in the suburban parks (Philopation, Aretai) and palatial gardens (Mesokepion, Mangana) of Constantinople.

The Byzantine garden tradition was influenced by the strong undercurrents of history that the empire itself was exposed to. The first and foremost influence was the adoption of Christianity as the empire's official religion by its founder Constantine I. The new religion signaled a departure from the ornamental pagan sculptures of the Greco-Roman garden style. The second influence was the increasing contact with the Islamic nations of the Middle East especially after the 9th century. Lavish furnishings in the emperor's palace and the adoption of automata in the palatial gardens are evidence of this influence. The third factor was a fundamental shift in the design of the Byzantine cities after the 7th century when they became smaller in size and population as well as more ruralized. The class of wealthy aristocrats who could finance and maintain elaborate gardens probably shrank as well. The final factor was a shifting view toward a more "enclosed" garden space (hortus conclusus); a trend dominant in Europe at that time. The open views and vistas so much favored by the garden builders of the Roman villas were replaced by garden walls and scenic views painted on the inside of these walls. The concept of the heavenly paradise was an enclosed garden gained popularity during that time and especially after the iconoclastic period (7th century) with the emphasis it placed on divine punishment and repentance.

An area of horticulture that flourished throughout the long history of Byzantium was that practiced by monasteries. Although archaeological evidence has provided limited evidence of monastic horticulture, a great deal can be learned by studying the foundation documents (τυπικόν, typikon) of the numerous Christian monasteries as well as the biographies of saints describing their gardening activities. From these sources we learn that monasteries maintained gardens outside their walls and watered them with complex irrigation systems fed by springs or rainwater. These gardens contained vineyards, broadleaf vegetables, and fruit trees for the sustenance of monks and pilgrims alike. The role of the gardener was frequently assumed by monks as an act of humility. Monastic horticultural practices established at that time are still in use in Christian monasteries throughout Greece and the Middle East.

Midieval Gardens

Monasteries carried on a tradition of garden design and intense horticultural techniques during the medieval period in Europe. Rather than any one particular horticultural technique employed, it is the variety of different purposes the monasteries had for their gardens that serves as testament to their sophistication. As for gardening practices, records are limited, and there are no extant monastic gardens that are entirely true to original form. There are, however, records and plans that indicate the types of garden a monastery might have had, such as those for St. Gall in Switzerland.

Generally, monastic garden types consisted of kitchen gardens, infirmary gardens, cemetery orchards, cloister garths and vineyards. Individual monasteries might also have had a "green court", a plot of grass and trees where horses could graze, as well as a cellarer's garden or private gardens for obedientiaries, monks who held specific posts within the monastery.

From a utilitarian standpoint, vegetable and herb gardens helped provide both alimentary and medicinal crops, which could be used to feed or treat the monks and, in some cases, the outside community. As detailed in the plans for St. Gall, these gardens were laid out in rectangular plots, with narrow paths between them to facilitate collection of yields. Often these beds were surrounded with wattle fencing to prevent animals from entry. In the kitchen gardens, fennel, cabbage, onion, garlic, leeks, radishes, and parsnips might be grown, as well as peas, lentils and beans if space allowed for them. The infirmary gardens could contain Rosa gallica ("The Apothecary Rose"), savory, costmary, fenugreek, rosemary, peppermint, rue, iris, sage, bergamot, mint, lovage, fennel and cumin, amongst other herbs.

The herb and vegetable gardens served a purpose beyond that of production, and that was that their installation and maintenance allowed the monks to fulfill the manual labor component of the religious way of life prescribed by Rule of St. Benedict.

Orchards also served as sites for food production and as arenas for manual labor, and cemetery orchards, such as that detailed in the plan for St. Gall, showed yet more versatility. The cemetery orchard not only produced fruit, but manifested as a natural symbol of the garden of Paradise. This bi-fold concept of the garden as a space that met both physical and spiritual needs was carried over to the cloister garth. The cloister garth, a claustrum consisting of the viridarium, a rectangular plot of grass surrounded by peristyle arcades, was barred to the laity, and served primarily as a place of retreat, a locus of the ‘vita contempliva’. The viridarium was often bisected or quartered by paths, and often featured a roofed fountain at the center or side of the garth that served as a primary source for wash water and for irrigation, meeting yet more physical needs. Some cloister gardens contained small fish ponds as well, another source of food for the community. The arcades were used for teaching, sitting and meditating, or for exercise in inclement weather.

There is much conjecture as to ways in which the garth served as a spiritual aid. Umberto Eco describes the green swath as a sort of balm on which a monk might rest weary eyes, so as to return to reading with renewed vigor. Some scholars suggest that, though sparsely planted, plant materials found in the cloister garth might have inspired various religious visions. This tendency to imbue the garden with symbolic values was not inherent to the religious orders alone, but was a feature of medieval culture in general. The square closter garth was meant to represent the four points of the compass, and so the universe as a whole. As Turner puts it,

"Augustine inspired medieval garden makers to abjure earthliness and look upward for divine inspiration. A perfect square with a round pool and a pentagonal fountain became a microcosm, illuminating the mathematical order and divine grace of the macrocosm (the universe)."

Walking around the cloister while meditating was a way of devoting oneself to the "path of life"; indeed, each of the monastic gardens was imbued with symbolic as well as palpable value, testifying to the ingenuity of its creators.

In the later Middle Ages, texts, art and literary works provide a picture of developments in garden design. During the late 12th through 15th centuries, European cities were walled for internal defense and to control trade. Though space within these walls was limited, surviving documents show that there were animals, fruit trees and kitchen gardens inside the city limits.

Pietro Crescenzi, a Bolognese lawyer, wrote twelve volumes on the practical aspects of farming in the 13th century and they offer a description of medieval gardening practices. From his text we know that gardens were surrounded with stonewalls, thick hedging or fencing and incorporated trellises and arbors. They borrowed their form from the square or rectangular shape of the cloister and included square planting beds.

Grass was also first noted in the medieval garden. In the De Vegetabilibus of Albertus Magnus written around 1260, instructions are given for planting grass plots. Raised banks covered in turf called "Turf Seats" were constructed to provide seating in the garden. Fruit trees were prevalent and often grafted to produce new varieties of fruit. Gardens included a raised mound or mount to serve as a stage for viewing and planting beds were customarily elevated on raised platforms.

Two works from the late Middle Ages discuss plant cultivation. In the English poem "The Feate of Gardinage" by Jon Gardener and the general household advice given in Le Ménagier de Paris of 1393, a variety of herbs, flowers, fruit trees and bushes were listed with instructions on their cultivation. The Menagier provides advice by season on sowing, planting and grafting. The most sophisticated gardening during the Middle Ages was done at the monasteries. Monks developed horticultural techniques, and cultivated herbs, fruits and vegetables. Using the medicinal herbs they grew, monks treated those suffering inside the monastery and in surrounding communities.

During the Middle Ages, gardens were thought to unite the earthly with the divine. The enclosed garden as an allegory for paradise or a "lost Eden" was termed the Hortus Conclusus. Freighted with religious and spiritual significance, enclosed gardens were often depicted in the visual arts, picturing the Virgin Mary, a fountain, a unicorn and roses inside an enclosed area.

Though Medieval gardens lacked many of the features of the Renaissance gardens that followed them, some of the characteristics of these gardens continue to be incorporated today.

Modern Gardens

In the 20th century, modern design for gardens became important as architects began to design buildings and residences with an eye toward innovation and streamlining the formal Beaux-Arts and derivative early revival styles, removing unnecessary references and embellishment. Garden design, inspired by modern architecture, naturally followed in the same philosophy of "form following function". Thus concerning the many philosophies of plant maturity. In post-war United States people's residences and domestic lives became more outdoor oriented, especially in the western states as promoted by 'Sunset Magazine', with the backyard often becoming an outdoor room.

Frank Lloyd Wright demonstrated his interpretation for the modern garden by designing homes in complete harmony with natural surroundings. Taliesin and Fallingwater are both examples of careful placement of architecture in nature so the relationship between the residence and surroundings become seamless. His son Lloyd Wright trained in architecture and landscape architecture in the Olmstead Brothers office, with his father, and with architect Irving Gill. He practiced an innovative organic integration of structure and landscape in his works. Subsequently Garrett Eckbo, James Rose, and Dan Kiley - known as the "bad boys of Harvard", met while studying traditional landscape architecture became notable pioneers in the design of modern gardens. As Harvard embraced modern design in their school of architecture, these designers wanted to interpret and incorporate those new ideas in landscape design. They became interested in developing functional space for outdoor living with designs echoing natural surroundings. Modern gardens feature a fresh mix of curved and architectonic designs and many include abstract art in geometrics and sculpture. Spaces are defined with the thoughtful placement of trees and plantings. Thomas Church work in California was influential through his books and other publications. In Sonoma County, California his 1948 Donnell garden's swimming Pool, kidney-shaped with an abstract sculpture within it, became an icon of modern outdoor living. In Mexico Luis Barragán explored a synthesis of International style modernism with native Mexican tradition. in private estates and residential development projects such as Jardines del Pedregal (English: Rocky Gardens) and the San Cristobal 'Los Clubes' Estates in Mexico City. In civic design the Torres de Satélite are urban sculptures of substantial dimensions in Naucalpan, Mexico. His house, studio, and gardens, built in 1948 in Mexico City, was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2004.

Roberto Burle Marx is accredited with having introduced modernist landscape architecture to Brazil. He was known as a modern nature artist and a public urban space designer. He was landscape architect (as well as a botanist, painter, print maker, ecologist, naturalist, artist, and musician) who designed of parks and gardens in Brazil, Argentina, Venezula, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, and in the United States in Florida. He worked with the architects Lúcio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer on the landscape design for some of the prominent modernist government buildings in Brazil's capitol Brasília.